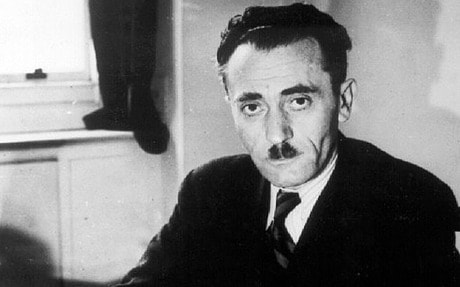

“I cannot stay silent and I cannot live while the remnants of the Polish Jewry are dying.” – Szmul Zygielbojm, 1943

According to the Genocide Convention, genocide means “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such”. In other words, acts intended to threaten a group’s existence constitute genocide.

In this light, it is clear that the Rohingya in Myanmar are victims of an ongoing genocide. They are being murdered, raped, starved, displaced and tortured. Their homes are being torched, their families are being separated and their livelihoods are being destroyed. Their very claim to exist as a people is being denied by the Myanmar state authorities, who target them because of their distinct ethnic and religious identity. Yet no major government or entity – not even the UN – has called it for what it is: a veritable genocide. Why is this?

Abdication of responsibility

The reason why governments are not using the word genocide is that doing so automatically gives rise to the legal obligation to actually do something about it. Article I of the Convention dictates that signatory states “confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.” In other words, all signatory states, all 147 of them, are legally mandated to prevent genocide from occurring and to punish those genocidaires who commit the crime.

There is also the moral imperative. When Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jew, coined the word in the mid-20th century – “geno” being Greek for race, “cide” being Latin for killing – his intention was to invent a word that would convey precisely the barbarity and totality of the crime the word describes. The word would be so disturbing, he hoped, that people and governments would do everything they could to prevent any future instance of genocide, including intervening militarily if necessary. After all, genocide is arguably the worst crime any state or people can commit. Romeo Dallaire, commander of the UN peacekeeping force in Rwanda during the 1994 genocide, calls genocide the “highest scale of crimes against humanity imaginable” – the Holocaust being the quintessential case.

The reason why governments are not using the word genocide is that doing so automatically gives rise to the legal obligation to actually do something about it

But what has happened is the exact opposite of what Lemkin intended. In the case of the Rohingya, major governments are refusing to say that genocide is going on precisely because of what doing so entails: a moral and legal responsibility to intervene. But because there is neither appetite nor intention to intervene in any meaningful way, the result is what we are seeing at this very moment: governments and international bodies obfuscating on the question of genocide, exclusively using the term ethnic cleansing instead.

“If you call it ethnic cleansing, it lets governments off the hook,” Professor Penny Green, international law expert, says. This is because ethnic cleansing does not carry weight in international law as there has never been a definitive description of what it is. Therefore, governments are happy to use the term, safe in the knowledge that they are not obligated to do anything about it.

Ethnic cleansing has thus become a euphemism for genocide. Here in the UK, the Foreign Office has stated that the government uses the term ethnic cleansing because they are in no position to make determinations about whether genocide is occurring in Myanmar. They argue that such decisions are reserved for international tribunals. What they fail to mention is the fact that it would take years for such tribunals to make their determinations – years the Rohingya do not have. In the US, only yesterday did the Trump administration describe events in Myanmar as ethnic cleansing for the very first time, when Secretary of State Rex Tillerson issued a statement condemning what he called “horrendous atrocities”. But even then, his statement was quickly followed by a senior official reminding reporters that ethnic cleansing is not defined in US or international law, therefore it does not “inherently carry specific consequences”.

Romeo Dallaire, commander of the UN peacekeeping force in Rwanda during the 1994 genocide, calls genocide the “highest scale of crimes against humanity imaginable”

All of this would be shocking were it not so familiar – for such obfuscation and evasion has been part and parcel of signatory states’ relationships with the Genocide Convention ever since its conception. In 1994, as the quickest and most efficient killing spree of the 20th century was underway in Rwanda (800,000 dead in 100 days), US officials busied themselves not with finding ways to stop the killing but with efforts to stop the g-word being uttered by any government official. The year before, as the Bosnian Serbs were raping, killing and pillaging its way through the Bosniaks during the Bosnian War, then-Secretary of State Warren Christopher had this to say when asked whether genocide had occurred in Bosnia-Herzegovina:

Tantamount to genocide, but not genocide per se. Such euphemisms provided yesteryear’s leaders the wriggle room needed to maintain a status quo of inaction in the face of grave injustice; such euphemisms are being invoked by today’s leaders for the very same reason.

Against the overwhelming evidence, our governments and politicians are refusing to utter the g-word as if their lives depended on it. As David Bosco puts it, this is a “warped diplomatic game” featuring politicians and their capacity for mental gymnastics, a game played at the expense of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya whose lives really do depend on them – and, the longer this cruel game goes on, undoubtedly more.

“The world watches and permits”

Szmul Zygielbojm, whose quote begins this article, was, like Lemkin, a Polish Jew and a member of the Polish government in exile during WWII. Like Lemkin, who lost 49 members of his family in the Holocaust, Zygielbojm also lost much of his family at the hands of the Nazis, including his wife and child who died in the Warsaw ghetto. In 1943, he committed suicide by ingesting an overdose of sleeping pills. But the deaths of his loved ones were not what drove him to suicide; rather, it was the indifference of the Allied governments in responding to the Holocaust that ultimately broke him. In his suicide letter, he wrote:

Never Again, the solemn promise made by the international community in the wake of the Holocaust, was made not only to those directly murdered by the Nazis. It was also made to those indirectly destroyed by dint of their families and friends being stripped from them – Zygielbojm, Lemkin and countless others. What the plight of the Rohingya tells us is that the promise has never rung so hollow, though perhaps even that is untrue, for the promise has arguably been moribund for decades. Just ask the Tutsis in Rwanda, the Darfuris in Sudan, the Kurds in Iraq or, especially today, the Bosniaks in Bosnia, whose chief persecutor Ratko Mladić, mastermind of the Srebrenica massacre, was finally jailed yesterday 16 years after the war. Are we really prepared to sit idly by and watch the Rohingya join this miserable list of persecuted people, an indelible stain in the pages of human history?

The recent decision by LSE students to strip Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s de facto leader, of her title as Honourary President of the Student Union was a no-brainer and a welcome development. But it is also a largely symbolic move – not a recommendation for a course of action, merely an expression of disapproval about what is going on in Myanmar. What needs to be done now is something of substance. That is why this publication is calling on the UK government to recognise the Rohingya genocide for what it is: a genocide. Though some might dismiss this as mere squabbling over lexical choice, it is not in fact trivial but hugely consequential the terms our leaders use to describe events in Myanmar, because of the reasons I have outlined.

Though we do not know with any certainty what the solution is, whether it be imposing more stringent sanctions or mounting a military intervention, what we do know is that such debates, of which there must be and be plenty, would be better served when had under a collective recognition of our responsibilities – as a signatory state of the Genocide Convention and as fellow human beings.