From the outside, it seems as if nothing has changed. For a brief moment, the world turned its eyes to the German election, noticed Merkel had won and then turned back to Trump and Brexit. Strong and stable leadership: what is but a dream for Theresa May seemed like an unquestionable reality for Angela Merkel. Well, not quite. In a way, it is true that the election was probably just a storm in a teacup; the general contours remain the same, spillover possible yet unlikely. However, this particular election has an interesting story to tell about the microcosm of German politics, which has just become a bit more colourful.

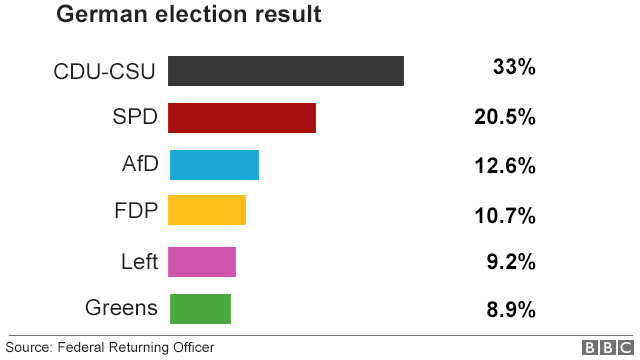

So what exactly happened on 24 September? Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU) and their Bavarian sister party (CSU) were, as expected, the victors of the evening. Their disappointing combined vote share of 32.9%, however, barely satisfied anyone. The result came about partially due to a considerable shift of votes to the right-wing populist AfD in East Germany as well as Bavaria. The second group of losers were Merkel’s coalition partners: the Social Democrats (SPD) attained 20.5% of the votes, their worst result since 1945. But most importantly, the election had two big winners: the AfD, who has now entered parliament for the first time, and the liberal FDP, who have returned triumphantly after four years of absence from an abysmal performance in the 2013 elections. The next governing coalition seemed to be clear the night of the election. Eliminating CDU coalitions with the Merkel-weary SPD, the far-left, and the far-right, only the Jamaica coalition remained. The expression stems from the colours of the included parties: the black CDU/CSU, the environmental Greens, and the yellow FDP – which mirror the colours of the Jamaican flag.

The next governing coalition seemed to be clear the night of the election. Eliminating CDU coalitions with the Merkel-weary SPD, the far-left, and the far-right, only the Jamaica coalition remained. The expression stems from the colours of the included parties: the black CDU/CSU, the environmental Greens, and the yellow FDP – which mirror the colours of the Jamaican flag.

To analysts used to two-party systems, this type of wide coalition may seem puzzling. Greens and Christian Democrats? Greens and liberals? What appears impossible is technically possible under what Politico calls “Germany’s consensus-driven political model”. At the state/Länder level, the diversity of coalition combinations is impressive: CDU and Greens; SPD-FDP-Greens (“the traffic light coalition”); CDU-SPD-FDP (“the Germany coalition”); SPD-Linke-Greens (“R2G”); CDU-SPD-Greens (“the Kenya coalition”) – and Jamaica. On the federal level, however, such a coalition has never been formed.

Exploratory talks – unofficial coalition negotiations – started towards the end of October. Merkel is facing a colourful set of negotiators. There is the new poster boy of the liberals, 38-year old Christian Lindner, who led his party back into parliament with bombastic rhetoric and a stylish PR campaign. Publicly he seems determined to become finance minister. Then, there are Cem Özdemir and Katrin Göring-Eckardt, the top candidates from the Green Party who set bold conditions for a coalition before the election. In practice however, they appear more willing to compromise, thereby risking a loss of credibility with their traditional left-wing voter base. Finally, Merkel’s seeming ally, the CSU leader Horst Seehofer, has proven himself a notorious troublemaker these past few years. Driven by the CSU’s losses to the AfD, he may become even more insistent on ultra-conservative policies like new limits to the rights of asylum-seekers – a topic excluded from discussion by all other parties.

There is great potential for a lot of disagreement, not only (but most pronouncedly) on the topic of refugees. Regarding environment protection, the Greens demand a fixed end to the combustion engine by 2030 and to coal power stations by 2060, to the collective horror of the FDP and the CSU. Correspondingly, first talks on these issues ended in a public quarrel raising initial doubts about the success of the negotiations. For now at least, further discussion of these problems have been postponed. Apart from a cross-party split regarding the environment, parties widely agree on the necessity for a law that allows more ‘organised’ immigration. Also, the need for investment into the formerly neglected sectors affected by digitalisation has been stressed.

Given the limited overlap of the parties’ preferences, the compromise could be based on the lowest common denominator. Merkel might thus have a fairly restricted scope of action for reforms. The prospects for the European project, for instance, are somewhat dubious. On one hand, Wolfgang Schäuble, unpopular in Southern Europe as a watchdog of European austerity, relinquished the post of the finance minister.

This is not exactly a strong and stable government, particularly when one considers the new players on the scene: 12% of voters opted for the AfD, marking 2017 as the first year that the far-right nationalists are entering the parliament in Germany since 1945. Correspondingly, they are met with outrage by the established parties. Even trivial matters such as which party has to sit next to the AfD in parliament sparked an ongoing row. Furthermore, nearly 77% of MPs refused to vote for the AfD’s candidate for the parliament’s vice-presidency, due to his controversial statements regarding the religious freedom of Muslims. Usually, candidates for this mostly ceremonial office, represented by one member of each party, are elected by cross-party consensus. At the same time however conservatives in the CDU/CSU have started campaigning for the parties to shift back to the right – that is, essentially, to copy the AfD’s positions.

Dealing with the AfD seems schizophrenic – even in the AfD itself. In what is declared to be a conflict between “fundamentalists” and “realists”, two MPs split from the main faction and formed the “Blue Party”: right-wing but not quite as right-wing. As a result, the number of party groups in parliament jumped from four in 2013 to six plus two independent MPs in 2017.

All in all, German politics are unlikely to change fundamentally after this election. From the outside, it might even seem as if nothing has changed. But the inside foreshadows the fragmentation that Germany will have to deal with when the framework of German politics is shattered in a post-Merkel world.