The Dandong “Friendship Bridge” on the China-North Korea border seems a fitting emblem of recent developments in China-North Korea relations. Constructed between 1937-43, the so-called “Friendship Bridge”, named thus in the 1990s, is a rickety, worn affair, which over the past few years has seen traffic notably curtailed. Although a new bridge, costing $330 million, was partially completed about a year ago, it now lies abandoned, with the North Korean side simply tailing off into some fields and no attempt to connect it to existing road networks in sight. The empty streets of Dandong and the murky silence of the Yalu river stand testament to the increasing distance between the two regimes in recent years.

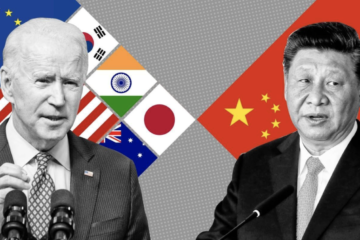

Though the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has often been seen as the “key” to the problem of North Korea, not least by US presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump, the truth is a little more complex. Similarly, Steve Bannon’s assertion that China can tame its “client state” fundamentally misjudges the long and difficult history of Sino-Korean relations. Although both China and the US undoubtedly wish to limit North Korean provocations, this belies a complex web of competing security interests. Certainly, while urging cooperation, both China and the US are prone to regular accusations of counter-productive pursuit of self-interest.

Regardless of what Mr Bannon might believe, since its inception the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) has sustained strained relations with China. Upon the DPRK’s founding in 1948, Kim Il Sung, the founder of the DPRK, immediately aligned himself with the Soviets and resisted Chinese aid, initially refusing to meet with Chinese military officers to discuss Korean strategy. The eventual, and somewhat unexpected, intervention of China a few months into the Korean War (1950-53) did, to some extent, repair relations between the two nations; yet even this was underpinned by Chinese strategic and diplomatic interests, and did not necessarily reflect a genuine concern for North Korean welfare. Relations further worsened during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-76) with the Korean Worker’s Party denouncing Mao Zedong, the Chinese leader, as “an old fool who has gone out of his mind”. In response the Chinese ambassador left Pyongyang in October 1966, and commerce between the two nations all but ceased. Ultimately, it has been an alliance of necessity, not desire, and since the Sino-Vietnamese War (1979) North Korea has had good reason to mistrust their reluctant friend, who had so readily turned on another erstwhile ally.

Though in recent decades relations had improved somewhat, the withdrawal of North Korea from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 2003 represented an unwelcome development for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). While China accounts for more than 90% of trade with the so-called “Hermit Kingdom”, since nuclear weapons testing began in 2006 China has been increasingly willing to support sanctions on the DPRK. Indeed, China supported the most recent round of sanctions, passed in the UN on the 11 September, which bans imports of coal, textiles and seafood, and more importantly limits oil shipments to the nation. This resolution (No. 2375) also bans DPRK nationals from working abroad and places heavier limitations on banks and companies working with North Korea. Nonetheless, China’s appetite for punishment is limited, and it only agreed to support this version of the resolution after certain measures were dropped, namely a complete oil embargo and authorisation to use force when ships do not comply with inspections. Despite these sanctions, China-North Korea trade increased almost tenfold from 2000-2015. It is difficult to know exactly what these new sanctions represent. While foreign observers have long been sceptical about China’s implementation of sanctions, there have been indications of change. China’s Ministry of Commerce temporarily suspended coal imports from the DPRK in February 2017 and Chinese coal imports from the DPRK have dropped 41% since last year; the state-owned National Petroleum Corporation suspended fuel sales in June 2017; and numerous banks (including China Construction Bank, Bank of China, and the Agricultural Bank of China) have restricted the financial activities of North Korean individuals and businesses. Ultimately, it is hard to discern whether these varied changes represent a strategic shift or a tactical one, whether China’s overall aims have changed or just the consensus on how best to achieve these aims.

Certainly, Chinese discourse on North Korea has soured over the years. Upon Kim Jong Un’s ascension, hopes for more positive relations were high, with the two nations agreeing to build high-speed rail networks together. Yet since 2013 Kim, now mocked by Chinese netizens as “Kim Fatty the Third” has behaved in a seemingly antagonistic manner towards the Chinese President Xi Jinping, first staging a nuclear test which coincided with Xi’s ascension, and then executing his own uncle Jang Sung Taek, who was one of the main channels for communication with China. Since then Kim has been openly condemned by the Chinese state press, with the People’s Daily accusing him of stirring up political instability after he visited a missile factory in March 2016.

Yet, despite this criticism, China has restrained itself from exercising the full weight of its power, continually refusing to cut off oil supplies to the DPRK. Many commentators have suggested that without this crucial step (China supplies more than 80% of the DPRK’s crude oil) existing sanctions will have little effect on the Kim regime. However, while further oil sanctions could mortally wound the DPRK, regime collapse is likely not in China’s best interest. China retains exclusive access to the DPRK’s natural resources, not restrained by any environmental or labour regulations. Furthermore, unlike South Korea, Japan and the US, North Korea does not necessarily present a direct security threat to China, and provides a buffer zone between China and American-backed forces. Certainly, China is wary of furthering US interests and recently suggested that the DPRK could be persuaded to halt further tests only if the US halted joint military exercises with South Korea and Japan. A large-scale confrontation on China’s border presents only danger, with the encroachment of US-backed forces and the potential for nuclear war. If the Kim regime were to collapse, this could mean millions of refugees streaming into north-east China, a race for North Korea’s nuclear arsenal, and a unified, pro-Western Korea on China’s border. As the DPRK increasingly becomes a threat not just to US allies, but to the US homeland itself, escalation seems ever more likely. Trump’s aggressive rhetoric certainly does nobody any favours. His statement to the UN General Assembly in September, that the US would have “no choice but to totally destroy North Korea” if it attacked American allies, will only worsen Chinese fears.

China alone does not have the power to force or negotiate a solution, and suggestions that they are entirely responsible for the escalating crisis are not only misleading but unhelpful. There is no simple solution to the problem, and assertions by the US administration that China “holds the key” are, in part, an attempt to shift the onus of responsibility away from the US. The response of the Chinese Ambassador to the US, Cui Tiankai, a few weeks ago provides a fairly good summation: “The US side said its strategic patience has run out. We hope it will lead to proactive actions on the diplomatic front, not strategic impatience instead”. Undoubtedly, there are signs of improvement on this front. In August 2017, top Chinese and US military officials agreed to further develop frameworks for cooperation, yet the risk of miscalculations remains high. Tensions between South Korea and China have risen markedly since the deployment of the THAAD missile defence system, yet here too there are signs of rapprochement [see ‘China, South Korea and a Straw Man’ to be published later this week]. Despite the assertions of Wang Yi, the Chinese Foreign Minister, that Xi is a transcendental “diplomatic pioneer”, perhaps it is better, for the moment, that the Chinese leader remains a bit more grounded in his aims. Undoubtedly, damaging Xi’s aspirations as a “global leader” is part of North Korea’s strategy, yet we would do well to remember that Xi is not the only leader failing to provide leadership on this issue.