Which country are you from? Hong Kong.

So you’re from China. Yes and no.

But isn’t Hong Kong in China? Yes, but they’re not the exact same.

But you have a Chinese passport? I don’t actually. I have a British passport.

Got it. You’re British. Technically yes, but I wouldn’t call myself British.

Hold on. So you’re Chinese but not really Chinese, British but not really British.

Yes, that’s exactly right.

***

The three allegiances that people from Hong Kong typically lay claim to are British, Chinese and Hong Konger. In recent years, the old British colonial flag of Hong Kong has increased in appearances at pro-democracy, anti-Beijing protests around the city – a development that has incensed mainlanders and Chinese officials.When protestors have been asked why they brandish flags which, for many, symbolise years of foreign occupation and oppression, they often answer with the retort that Hong Kong is still being subject to the control of a foreign power. The only thing that has changed is the country doing it. At least the British acknowledged that they were ruling us, they say.

Though my parents would never go so far as to publicly declare allegiance to the British, they, like many Hong Kong people, retain some level of nostalgia for the days of British rule. When the last British Governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten, returned to the city post-handover for a book tour, my parents, serious civil servants rarely flustered by any celebrity news or happenings, made sure our entire family was first in line at the signing event. The occasion was captured by picture and frame which still hangs prominently on our living room wall.

In fact, the former Governor is invariably swarmed by crowds armed with colonial flags whenever he returns to the city, typically to cries of adoration and pleas for help.

I was born in Hong Kong in 1996, which means that I was born into the twilight months of British colonial rule. Twenty years ago today, the city was handed back to China, a day which many also consider to mark the end of the British Empire when the sun did finally set on it for good. Though those months now lie beyond the reach of memory, the spectre of the British has followed me ever since in the form of the British passport I hold.

The benefits of possessing one of the most powerful passports are obvious, but it presents some difficulties as well. Specifically, difficulties to do with identity, a problem which has in recent years come into sharp relief. I acutely remember the first time I was acquainted with the British national anthem after moving to the UK, and the discomfort I felt as I contemplated whether or not to sing along. Though I am technically British, calling myself British was as alien a thought as calling myself Rwandan. And so I didn’t sing along.

But that experience got me thinking: which country do I associate with? Which national anthem should I sing?

Identity confusion

Anyone from Hong Kong can tell you that every night, the major TV networks are all required to blare out the March of the Volunteers – China and therefore Hong Kong’s national anthem – along with slick video promoting the nation. But in an ironic twist of familiarity breeding contempt, the daily dose of propaganda has inculcated a deep disdain amongst some Hong Kong people, particularly the young, for a Mandarin anthem which isn’t even sung in the same language that Hong Kong people mostly speak.

Last year, the Hong Kong Football Association was fined by FIFA because Hong Kong’s fans have consistently booed their own national anthem before games. Fans have even turned their backs when the song is played, preferring instead to sing local Cantonese songs. This should be unsurprising given that only 3% of young Hong Kong people today identify as Chinese or broadly Chinese, a historic low that runs counter to the prevailing belief two decades ago that Hong Kong will grow closer to China with the passing of time. What has happened is the exact opposite.

Does this suggest that Hong Kong people want to become independent from China? Recent polling would suggest otherwise, with just one in six supporting outright independence, and even fewer who think that it will actually happen. However, the city’s pro-independence movement is stronger than it has ever been, particularly amongst the youth, as demonstrated by the stunning legislative election victories of several radical pro-independence activists, the youngest of whom just 23 years old. These victories naturally alarmed Beijing who quickly intervened and stripped the activists of their seats.

For many of the city’s youth, independence is the obvious path to take to detach itself from the oppressive grip of Beijing. But for just as many Hong Kong people, not only is seeking independence a fool’s errand but also a near-treasonous act of turning their backs on fellow countrymen. The generational divide on this issue is clearly demarcated. Older generations are more likely to have been born and raised in the mainland. They probably relocated to Hong Kong later in their lives or have parents who deeply identify as Chinese. In contrast, many young Hong Kong people do not have significant ties to the mainland and maybe even, like me, hold a passport not of the “motherland”.

The strife in Hong Kong society today can be viewed as a fervent debate over the identity of the city, not dissimilar to revolutions in the past and present. In October this year, Catalonia will hold a referendum on independence from Spain, a region like Hong Kong in that both have cultures, histories and languages different from their respective mainland. Singapore is another example which many pro-independence Hong Kong people like to highlight. The two cities’ similarities in size as well as the comparative size of their “unsavoury” neighbours (Malaysia in Singapore’s case) makes Singapore a beacon of hope for many pro-independence activists.

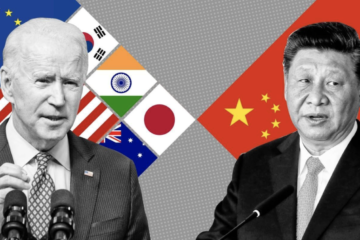

The question of what country to identify with is not an easy one to answer, not for me and not for Hong Kong either. A complicated history of decades of British colonial rule and now the spectre of perpetual Chinese oversight means that the city seems to be irrevocably pitted into opposing camps: those who see themselves as Chinese and those for whom such a title represents the antithesis of their deepest values.

For many years, Hong Kong’s tourism board has proudly declared the city to be “Where East Meets West”, encapsulating it’s melting pot of Western influences and Eastern sensibilities. Perhaps it is not so surprising that such an eclectic place is finding it difficult to come to an agreement about which side the scales tip when it comes to its identity.