It took three days and 20 deaths to see the siege which engulfed Paris come to an end. ‘Ironic’ cannot begin to describe the sequence of events which followed Stephane Charbonnier’s or ‘Charb’s’ illustration in his last edition of Charlie Hebdo. The killing of journalists, a caretaker and a policeman at the satirical publication on Wednesday, in addition to subsequent shootings and hostage-takings over the next two days, shook not only Paris, but those in solidarity around the world. This attack on outspoken proponents of democracy has been denounced by all, excluding the network of extremists who claim to be fighting in the name of Islam. But how can this violent cause be conflated with a peace-loving religion? With regards to the murdered police officer, Ahmed Merabet, how can it lead to the killing of those with whom you wrongfully and insultingly associate with?

Last Sunday’s ‘Marche Republicaine’ saw almost 4 million demonstrators including 70 world leaders proclaim ‘we are not afraid’, most notably through the adoption of ‘#JeSuisCharlie. Yet, almost as quickly as the ‘#JeSuisCharlie’ hashtag emerged online, so did criticisms towards it. What many expressed after the killings was that Charie Hebdo, despite being a satirical magazine, used this label to disguise underlying racism and Islamaphobia. Although the magazine’s illustrations are devoid of political correctness often provocative, as widely remarked by journalists and the late Charb himself, all sectors of French society were targeted equally by the magazine.

We cannot eliminate the issue of culture: France is a country in which freedom of speech is exercised as fully as possible. It is no coincidence that a British equivalent of Charlie Hebdo does not exist in the mainstream; it certainly would not live to compete with Charlie’s forty-four year presence in the media. Aptly, the famous Voltaire quote: ‘I do not agree with what you have to say, but i’ll defend to the death your right to say it’ has been adopted by many and reflects the respect that societies around the world express towards the freedom of expression, despite the controversy surrounding it. Undeniably, the images depicting the prophet Mohammed were offensive and in bad taste. However, it in no way justifies confrontation to this extent. That is not Islam.

A principal concern of the French population, Muslim and non-Muslim, is the potential ‘amalgam’ which is anticipated to follow. I, along with most, fear for the plight of the Muslims who may find their position in French society in a vulnerable state. Already, ‘revenge’ attacks against mosques and innocent Muslims have taken place, only serving to heighten religious and cultural tensions, and add fuel to the fire of ignorance. Blaming the majority of followers of Islam is both irresponsible and vilifying.

In contrast to #JeSuisCharlie, ‘#JeSuisAhmed’ has also been been used to voice the heroism of the murdered policeman who many remarked was ‘protecting a magazine which made fun of his religion’. The hashtag also marks the position of Muslims and non-Muslims alike who, although sympathising wholeheartedly with victims of the attacks, do not accept the depictions of the Prophet Muhammad published by Charlie Hebdo.

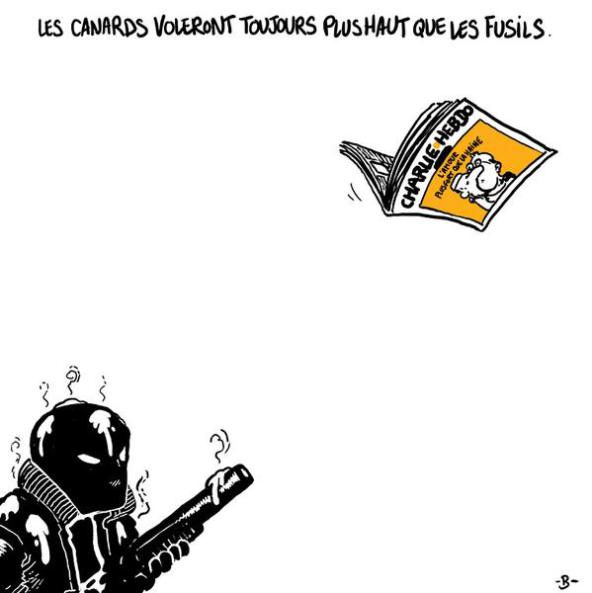

Over the days following the killings in Paris, pictures on the French news channel ‘France 2’ showed measures taken by teachers to educate and debate with students on the implications of such an attack. One picture which struck me was of a teenage girl weeping, overwhelmed by what she saw as a ‘war’ breaking out. What the peaceful protests have shown yesterday, today and I hope tomorrow, is that we are not at war in terms of deadly weapon against deadly weapon. Right now, we are fighting with our pens and pencils, defending our right (to the death) to use them, and to exercise freedom of speech.

In the same vein of democracy and freedom of expression, it seemed contradictory to exclude Marine Le Pen’s ‘Front National’ from participating in Paris’s upcoming national unity rally. However, this was a very welcome contradiction, and it spoke volumes: while Le Pen could use the attacks to further her political agenda, her ability to do so is being restricted. The core-rattling events witnessed over these past few days nearly always engender a strong unity and nationalism within the affected country, and it is reassuring to witness that, publicly, Islamophobia has no place in it. Privately, however, we must not be under the illusion that ‘unity’ is our reality – it is not. Europe is a deeply fractured continent, and, as the Pegida movement in Germany shows, Islamophobia is a profoundly rooted problem which governments and citizens must actively work to rectify.

Beyond these protests however, we also cannot ignore the wider issue of extremism, its advocates, and the dangers it presents in the future. It has been said that the attack on Charlie Hebdo is a French equivalent of September the 11th; one of the most poignant illustrations published as a response to Wednesday’s attack is a symbolic representation of 9/11. In it, two green pencils stand upright, with a plane heading towards them. Given the comparisons made between the two era-defining attacks, it is yet to be seen whether the cause of action which follows Wednesday’s attacks will mirror that of 9/11.

In proclaiming ‘Je Suis Charlie’, supporters are standing in solidarity with the principles of a publication which fully exercises freedom of speech, as well as its victims and their families. Yes, the magazine is polarizing, and often as ‘nasty’ as it proclaims itself to be. But ultimately, the freedom of speech – this ‘pillar of democracy’ – is one which we must defend our right to exercise. Journalists of Charlie Hebdo cannot be blamed for their deaths, for such extreme defensiveness can never be justified – and certainly not in the name of Islam.