In the modern age of short news cycles and even shorter attention spans, things that ought to shock and disturb us are quickly accepted as the new norm. I could list off Trump’s indiscretions: his contempt for the rule of law, open admiration of tyrants, sheer ineptitude, dishonesty, but even that would not come close to communicating the scope of his failures as president. What’s more, it would be boring! The President of the United States bragged that he fired the head of the FBI who was investigating him for colluding with a foreign power to get elected. We hardly talk about that right now because he does something comparably appalling every week. This is the world we live in.

We cannot be distracted by Trump’s persona from the forces that carried him to high office. He was not merely a person with ‘talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity’, as Alexander Hamilton put it — there are many of those. It is vital that we understand how Trump took over the Republican Party so that never again is a major party captured and redefined by its worst elements.

The dominant school of thought on this matter is disappointing. It would tell us that Trump is an aberration, thwarting the Republican mainstream, with no relation to those that came before him. Most pieces tackling this subject, such as David Brooks’ writing on ‘The Conservative Intellectual Crisis’, read as sappy requiems for a golden age of Republican intellectualism. It suggests that if only there were modern equivalents of these high priests of conservative insight, the GOP would have remained a creative and effective governing body:

This is not to say that the conservative intellectuals in question would have approved of Trump – I am entirely sure they would not. Trump’s first foray into politics was meddling in the Reform Party’s 2000 primary, after which William F. Buckley derided Trump as a demagogue and a narcissist.

Donald Trump is at face value very different to any previous Republican president, but to focus on this fact obscures Trump’s vast intellectual debt to the ostensible ‘golden age’. Trump does not exist because of the lack of conservative intellectuals — rather the intellectuals of the golden age created a flawed movement and watched it slowly become more vacuous and immoral for political gain. They now find themselves in history as the unwitting architects of the man in the White House and the culture that made him possible.

Our story begins in the 1950s, as twenty years of uninterrupted Democratic control of the White House came to an end. The GOP faced a question of existential importance: did they oppose the New Deal? The American people elected Dwight Eisenhower, who represented the moderate wing of the Republican party. He did not oppose the New Deal. Rather he resigned to promising to run it more efficiently, and even expanding programs like social security.

Trump does not exist because of the lack of conservative intellectuals — rather the intellectuals of the golden age created a flawed movement and watched it slowly become more vacuous and immoral for political gain.

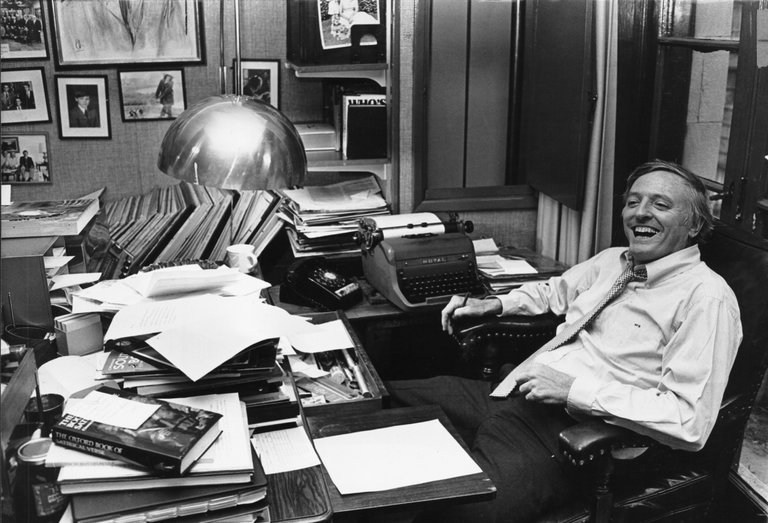

In 1950, Lionel Trilling wrote that the conservative movement had no ideas, rather only “irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas”. This changed largely because of one man, William F. Buckley. Seeking to oppose the New Deal and create what he would refer to as the “capital C Conservative” movement (henceforth referred to as ‘Conservatives’), he assembled an eclectic group of writers, anti-communists, libertarians, Catholic writers and traditional conservatives to form his new magazine, The National Review.

The mission statement of The National Review remains a fascinating read, typical of the bombastic and literary style pioneered by Buckley. It frames the magazine as “standing athwart history yelling: ‘Stop!’” However, even in its overture we find vulgarities in the Conservative movement sometimes thought to be exclusive to the Trump era. Notably a reflexive distaste of universities, modern art, as well as the paranoid belief that they are either being ‘suppressed or mutilated by the Liberals’ or ‘ignored or humiliated’ by more moderate conservatives.

It sounds almost paradoxical to accuse Buckley, the great Conservative intellectual, of being anti-intellectual, and yet the evidence is undeniable. Most notable is his affirmation that he would “rather entrust the government of the United States to the first 400 people listed in the Boston telephone directory than to the faculty of Harvard University”. Moreover, he derided any intellectual of the post-war Keynesian consensus or anything seen to be vaguely Postmodern, sure of himself that these views were driven by some insidious urge for collectivism rather than earnest academic inquiry.

This is especially strange considering several of the founding writers of the National Review — Russell Kirk, James Burnham, and Frank Meyer — were some of the leading conservative political theorists of their time. What this suggests is that Buckley was an anti-intellectual in his curation of intellectuals to listen to: that is to say he used the academy in the way a drunkard uses a lamppost, for support rather than illumination. There are clear parallels in this behaviour and that of the modern Republican party, denying human contribution to climate change being the obvious example, but recall too the Flint water crisis in which Republican Governor Rick Snyder contested the fact that lead ingestion was really a health hazard at all. The Republican Party is happy to listen to economists like Greg Mankiw and Martin Feldstein when they argue for tax cuts, but curiously their proposal for a tax on carbon emissions fell on deaf ears. Even the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, John Roberts (appointed by George W. Bush), is not immune to this. In a gerrymandering case earlier this year, he referred to an attempt by political scientist Eric McGhee and law professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos to quantify partisan bias in district mapping as ‘sociological gobbledygook’.

Eisenhower’s presidency comes to an end and the Democrats now control the White House. Lyndon Johnson wrestles the democratic party from Southern Dixiecrats to the benefit of the northern liberals. He is fighting to get his civil rights bill through Congress and his proposed Great Society reforms are framed as a second round of the New Deal. This period is important as Republicans, particularly the staunch Conservatives, developed a language of codes, designed to appeal to southern racists (former Democrats), while being imperceptible to moderate white voters. This move from the explicit racial language of the 50s to ‘Dog-whistle’ politics was described in a 1981 interview by leading GOP strategist Lee Atwater as such:

There is a certain nuance to this part of the story. Buckley himself was undoubtedly a racist, defending segregation and white supremacy in his galling 1957 editorial, “Why the South Must Prevail”. Yet a considerably higher proportion of Republicans voted for the 1964 Civil Rights Act and, for the moment, the GOP was still the relatively less racist party. This gave some plausible deniability to Buckley and the Conservatives: they could mock the Democrats purging their party of racism as racists while mastering the art of coded racial appeals to pick up these voters.

Nixon is elected in 1968 and manages to win Buckley’s affection despite governing from the moderate wing of the party. Nixon was still influential in the Conservative movement because of his boundless talents for political opportunism. Nixon popularised the notion of ‘law and order politics’, in reference to his support of brutal policing methods and spying by Hoover’s FBI to suppress the black civil rights movement. In July of last year, Donald Trump declared: “I am the law and order candidate”. In a campaign event in Nevada, Trump was entirely transparent in his nostalgia for the time in which open violence was commonplace, “…I love the old days. You know what they used to do to guys like that when they were in a place like this? They’d be carried out on a stretcher, folks”. Or in Fayetteville, North Carolina, he suggested in response to a Black Lives Matter protest that

Trump’s only innovation in the realm of dog-whistle politics is his occasional tendency to make explicit what was once coded. One can hardly stop from wondering whether making America great again involves ridding us of our reticence for violence, especially against minorities, but Trump makes it clear. The slogan “Make America Great Again” was in fact also used in Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign. That is the perplexing thing about conservatism, or ‘standing athwart history yelling: “Stop!”’. It appears initially as though Trump is nostalgic of the Reagan years, but Reagan himself was nostalgic of some other ostensibly halcyon age of days gone past. Then one realises which group can have genuine nostalgia for the era of Jim Crow, and the message becomes clear.

Reagan was the ultimate manifestation of Buckley’s ideology, and in him we find the Conservative movement’s final gift to Trump and the modern Republican party: fatuous and deceitful policymaking. Irving Kristol, another one of the Conservative sacred cows, was entirely clear on the dishonesty behind much of Reagan’s tax reform, “I was not certain of its economics merits, but quickly saw its political possibilities”. The idea that tax cuts could pay for themselves was known, in the more self-aware Conservative circles at least, to be untrue all along:

It is hardly surprising, given that conservatives were so comfortable prioritising political effectiveness, that the GOP could not come up with a replacement for Obamacare, despite 7 years of campaigning on the promise to do so. Neither is it surprising that they continue to peddle their regressive tax cuts with the same promises despite Kansas having clearly implemented the policies with the exact result one might expect.

Trump’s only innovation in the realm of dog-whistle politics is his occasional tendency to make explicit what was once coded.

It is not even clear that Trump himself is a Conservative: he seems more motivated by self-interest and his ego than anything else. Rather, I argue that the Conservative moment many are nostalgic for already had the seeds of Trump’s vices, where the importance of ideas are diminished and electability was prioritised. A movement that has been hollowed out as a vehicle for electoral gain is going to be attractive to a narcissistic demagogue.

If the Republican Party is to continue to exist in its current form, which is likely due to the two-party system, then it must respond to criticism not with a wistful invocation of some golden age but a sober recognition that Trump does not exist independently from history. There are currently some promising Republican politicians in this regard — John McCain gave a speech recently defending global political and economic institutions, proclaiming that America is “a land of ideals, not blood and soil”. That said, McCain is nearing retirement, and the Never Trump coalition seem much more marginal now than a year ago.

It is unclear how the Republican Party should change going forward and it seems that any attempts to do so will make them much less electable. However, two steps that must be taken are to allow the moderates to become prominent in the party again, rather than deriding them as RINOs (‘Republicans In Name Only’), or in modern parlance, “Cuckservatives”. Secondly, they must take down their shrines of Buckley and Kristol and confront their history face to face, uncomfortable as the results may be.