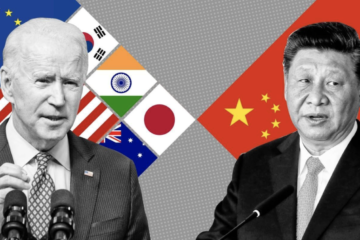

This Tuesday I went to see one of LSE’s public lectures entitled: ‘The Foreign Policy Dilemmas of the US Administration in the Next Four Years.’ The speaker was Professor John Coatsworth, provost and professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University. The lecture was incredibly interesting, with Professor Coatsworth doing his best to cover future American foreign policy in the Middle East, Asia and Latin America in the short space of an hour. Of course, there were some predictable moments, but this was largely because US foreign policy in the next four years will remain predictable: most of its foreign policy actions will be directed mainly towards the Middle East, and it will have to pay increasing attention towards the ‘pivot’ to Asia.