Chile has been labelled the ‘South Korea’ of Latin America and is often cited as the region’s paragon of free-market economics. Over the course of 40 years, Chile has developed from being one of the poorest South American countries to one of the most prosperous in terms of GDP per capita and is now considered a high-income country by the World Bank. Its track record of low inflation, little corruption, and prudent fiscal policy has earned Chile a place among Forbes’ top 30 countries for business, easily outranking 73-placed Brazil. Although the country has recently been troubled with stagnant economic growth due to declining copper prices, historically-speaking it has weathered economic storms more successfully than its neighbours. Throughout the crisis-prone period between 1985 and 2000 its growth rate hovered at an impressive 6.2 percent, compared to Brazil’s average of 2.8 percent.

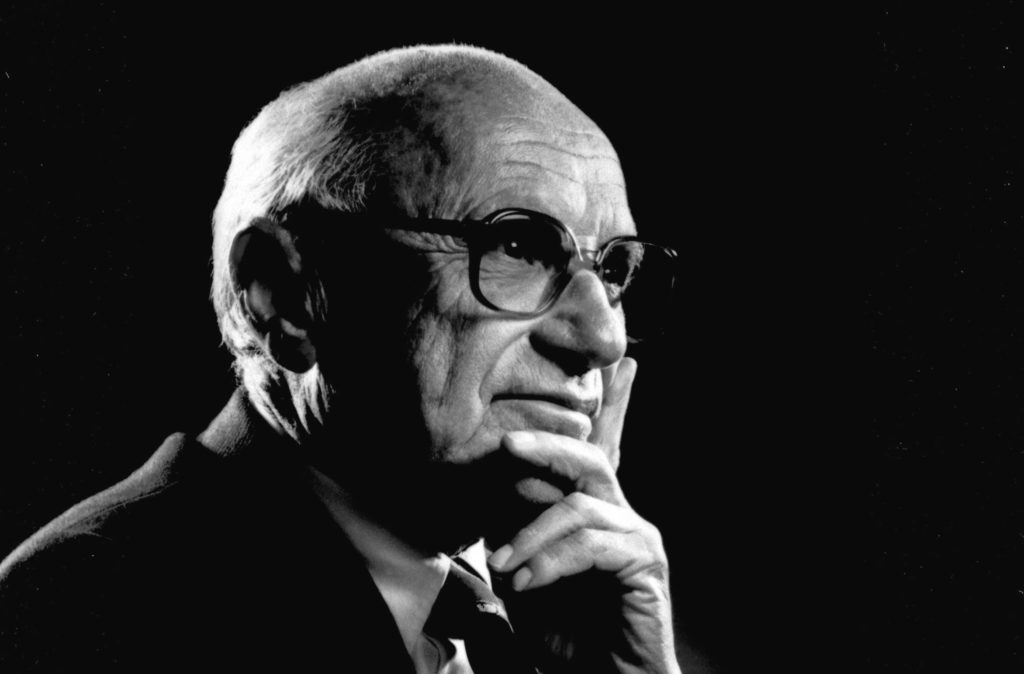

Chile’s economic success has conventionally been credited to the Chicago Boys, a group of Chilean economists who were – like Guedes – trained under Nobel laureate Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago. Upon Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état in 1973, the Chicago Boys were appointed to remedy Chile’s economy that suffered from hyperinflation and a budget deficit amounting to 25 percent of GDP – a legacy of president Salvador Allende’s socialist administration. The Chicago Boys’ vision of economic development centred on radical free-market policies: they convinced Pinochet to abolish the minimum wage, privatize the pension system, slash business and wealth taxes, and liberalize capital markets.

This textbook version of laissez-faire economics bears stark resemblance to the policies that Guedes has advocated for Brazil. In his inaugural speech on 3 January, the Chicago alumnus restated his commitment to privatize state-owned enterprises and overhaul Brazil’s pension and tax system. Fiscal sustainability is urgently needed to tackle Brazil’s fiscal deficit, amounting to 7 percent of GDP. Part of the debt has arisen from the country’s generous pension spending, which allows citizens to retire in their 50s at the expense of more than 11 percent of GDP. To close the fiscal gap, Guedes is also urging privatization of the 138 state-owned companies on the federal level including oil giant Petrobras, utility firm Eletrobras, and Banco do Brasil, Latin America’s largest bank in terms of assets. Privatizations are expected to tackle Brazil’s long history of corruption that culminated in the Operation Car Wash Scandal and the impeachment of president Dilma Rousseff in 2016. Supporters of Guedes’ pro-business agenda also hope that revenues will create infrastructure, increase efficiency, and expand support for start-up investments to turn Brazil into a fast-growing economy.

Yet, turning the clock back to 1982 reveals that Chile’s radical free-market experiment that Guedes wants to duplicate was not the economic miracle he has painted it to be. The strategy was ultimately a failure. The abrupt removal of import restrictions exposed the Chilean industries to strong international competition. A fixed exchange rate and an overvalued Chilean peso rendered Chilean goods less competitive, leading to reduced export earnings. When the US raised interest rates in 1982, high indebtedness combined with the overvalued exchange rate forced Chile to default on its debt. The economy crashed. Instead of economic prosperity, the neoliberal experiment had bestowed Chile with an even higher indebtedness, a ten-fold increase in unemployment, and an economy dominated by an oligopolistic conglomerate of businesses. The neoliberal shock therapy had increased the number of Chileans living in poverty from an initial 17 percent in 1969 to a staggering 45 percent in 1985. Although neighbouring countries were suffering similar debt crises, none of them reached the height of Chile’s, which caused an 11 percent drop in GDP.

The conditions under which Guedes will operate in contemporary Brazil are certainly different from those the Chicago Boys faced in Chile in the 1970s. Implementing free-market policies might be less of a shock treatment for Brazil’s economy, which is considered one of the most diversified in Latin America. In 1980 as today, exports in Chile were largely dominated by copper. On the other hand, the composition of Brazilian exports as of 2016 proved to be fairly diversified, consisting mainly of soybeans (ten percent of total exports), iron ore (7.4 percent), and raw sugar (5.7 percent). Moreover, the surge in the stock market and the Brazilian real that followed Bolsonaro’s election indicate that foreign investors have reacted positively to the proposed privatizations and support the neoliberal turn.

Yet, other factors that set the Chilean experience apart from contemporary Brazil may not work to Guedes’ advantage. Under the dictatorship of Pinochet, Chile was a blank canvas that the Chicago Boys could design without having to confront opposition parties, Congress, nor democracy. The Pinochet administration capitalized on oppression, leaving thousands of Chileans dead. If he wants to uphold democracy, Brazil’s new finance guru will face a much more difficult task. Pushing through his pension reforms will require a three-fifth congressional majority, which he will have to attain in the world’s most fragmented Congress. Amongst the 30 political parties represented in Congress, Bolsonaro’s Social Liberal Party (PSL) holds less than 10 percent of the seats. Also, Brazil’s Supreme Court is known for challenging privatizations, having ruled in June last year that selling public firms will require congressional approval. Whether such an environment will allow Guedes to pursue an unpopular economic agenda is questionable given his lack of political experience.

As for Pinochet, he soon replaced the Chicago Boys and reverted to less radical economic policies. In 1982 he nationalized major banks, reintroduced minimum wages and reinstated support for exporters and R&D. His capital account controls survived until the late 1990s, making Chile one of the few countries in the Western hemisphere that continued to restrict the inflows of capital until the turn of the century. Pinochet’s Keynesian antidote soon paid off. Backed by increasing copper prices that the government secured through state-owned copper giant Codelco, Chile jump-started its way out of the crisis with the remarkable growth rates the country has become known for.