Do you know how your phone is made?

Two major advances have dominated the tech scene in the last decade – the mass adoption of mobile phones and the progressive shift towards electric mobility, which have respectively induced a structural reconfiguration of social norms and urban planning. Cell phones are now indispensable in enabling worldwide connectivity and rapid accessibility of information, and act as agents of development in poorer parts of the world, with the potential benefits of online banking, education and governance. Electric vehicles (EVs) foster the transition towards clean energy, responding to challenges posed by greenhouse gas emissions and the obsolescence of natural resources.

Cobalt mine controlled by armed forces in eastern region of Kivu. Photo: Eric Feferberg/AFP/Getty Images

A greener, more equal world is undoubtedly a positive framework for innovation, and this is what these commodities strive for. However, would we as consumers persist with such rhetoric if we knew that large scale mining and human rights abuses directly degraded the environment? Some would choose to ignore this in favour of the environmental benefits, which is not wrong , but we should question the methods employed throughout this technological and environmental ‘transition.’ Do the ends justify the means? The environmental question can improve the very mechanisms of society.

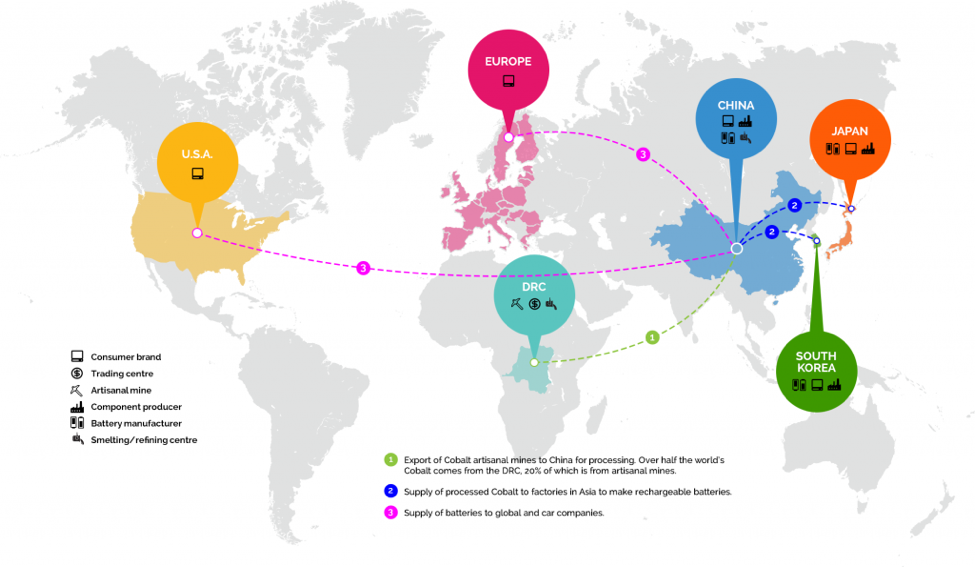

For the model to be coherent, we must reconsider one essential part of these two commodities; the battery. If one were to dissect a Tesla or iPhone battery, an array of precious metals would be sitting there: lithium, aluminium, and nickel. Within the cathode of the battery, there is the most expensive and rarest of them all: cobalt. This brittle black metal, at times labelled the Blood Diamond of Batteries, has already doubled in price since 2015, while its global demand will have tripled by 2030 (European Commission Science and Knowledge Service). While most batteries are built in China, 65% of the world’s cobalt reserves are located in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The problem is that the country is torn by civil unrest and human rights violations; worse still, the mining industry lies at the very roots of such instability.

Violence for control

In the eastern and southern regions of Ituri, Kivu and Katanga, far from the DRC’s metropolises and at the border of five countries, mining has come to represent the country’s twenty-year long conflict. When Laurent Desire Kabila overthrew the autocratic rule of Mobutu Sese Soko during the First Congo War in 1997, neighbouring Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda financed armed militias in direct support. Once Kabila took control of the country, a heterogeneous group of militias remained in the east,representing the state, non-state and foreign entities, reaping the benefits of the DRC’s natural resources. From this point on, artisanal mining (AMs) has developed exponentially, paving the way for smuggling of minerals into neighbouring countries, control of mines by armed forces, as well as corruption and lack of public traceability.

Today, the presence of Rwandan and Congolese armed militias (FDLR, CNDP) and the export of minerals are inextricably linked. Control of the mines by militias finances the perpetuation of conflict in the eastern and southern regions, which has led to civilian deaths, mass malnutrition and the displacement of over 4 million people from their homes since 2003.

The effects of mining on arable land – this is an exponential sector of activity. Photo: Bloomberg/Getty Images

Within the AMs themselves, which are said to employ around a fifth of the Congolese population (Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative), human rights violations are commonplace. Tens of thousands of workers are children, working in deplorable conditions for low pay ($1 to 2 USD per day). Constant contact with cobalt causes long term health damage, including respiratory sensitisation and decreased pulmonary function. A Sky documentary has shown children as young as 8 receiving physical blows from supervisors. Women in the AMs face sexual and gender based violence (SGBV), as well as lower pay, the proliferation of STDs through prostitution and miscarriages due to stress or malnutrition.

To add to this, mining in itself is the prime motor of environmental damage in the DRC. Mass deforestation to make space for mines degrades Congolese biodiversity, the disposal of waste into rivers contaminates water and dust pollutes the air. Land otherwise suitable for agriculture is rendered obsolete. Where farmers could contribute to the economy and promote development, most resort to work in the mines, with food scarcity a direct consequence.

In its supplying of a sustainable model in the United States, Europe and parts of Asia, the DRC is destroying its own wildlife. If demand is truly to soar in the next years, sustainability must come into play.

Stagnation of the masses, growth of the few

Sitting atop treasures that are the envy of all of sub-Saharan Africa, is it not paradoxical that the DRC remains at 176 out of 188 countries on the Human Development Index? It appears that this constant stagnation stems in part from the kleptocratic state’s handling of mining revenues. Since the 1960s’ mass nationalisation of mining companies, the trend of all regimes has been to amass fortunes through ownership of businesses. To this day 80% of the DRC’s revenues come from mining, and heads of state have always controlled this sector for their personal enrichment. A 2016 report by the NGO Global Witness suggests that only 6% of the annual $10 billion USD generated through minerals reaches the country’s public budget, with royalties from private international mining companies failing to find their way to the national treasury. Between 2013 and 2015 alone, $1.3 billion USD of mining revenues were estimated to have gone missing. This equates to the country’s cumulative health expenditure per person in 2015, the second-lowest in the world (World Health Organization).

International presence and solutions

For the DRC to exit this unsustainable resource-dependent cycle, several actors must alter their approach to the market. With regards to the state, agencies controlling the transfer of royalties from mining revenues must assure transparency and promote investment which benefits the Congolese people, in infrastructure, public health and education. Felix Tshisekedi, the first elected president since 1960, took over from Joseph Kabila in January 2019. If not a mere instrument of his predecessor, he will work towards economic recovery. The recent suspension of senators accused of accepting bribes from Kabila is a first suggestion that he will not accept blatant corruption.

International corporations, however, can lead the fight against human rights violations. Certainty that their cobalt provenance is conflict-free must be a priority. Some companies are noticing that the guarantee of a clean supply chain has become a major consumer preoccupation. Consumers must be given a coherent message regarding SDGs. Driving an electric car cannot come at the expense of a population’s quality of life. Here lies a great opportunity in the expansion of environmental consciousness worldwide: true ethical considerations within the private sector.

Cobalt’s journey before ending in phones and EVs, Photo: Taruga

The largest cobalt buyers in the DRC, primarily Chinese companies, are thought to combine cobalt from both regulated and artisanal mines, without considering conditions prior to distribution. Once shipped to China, it is very difficult for international tech and EV firms to trace the origin of the cobalt. Most companies are aware of the realities of the DRC’s mines. One solution, proposed by Apple and Samsung, is to buy cobalt directly from the miner. This would assure conflict-free cobalt and contribute to the royalties gathered by the state. Apple also launched a programme that teaches children other skills than mining, such as sewing or farming. The mines’ pay remains more attractive though, and according to Fortune, often provides for the subsistence of entire families.

Whatever the case, the Congolese model must be transformed. Elon Musk recently stated that Tesla is looking to make cobalt free vehicles in its next generation – this is unlikely for most companies in the foreseeable future, nor should it be desired. The complete boycott of the DRC would only aggravate the living environment and the economy would take a major blow. Each actor along the supply chain has a role to play. Currently, Tshisekedi is working to make the Congolese mining sector more attractive to foreign investment, following meetings with mining companies Glencore and Barrick Gold in March. This must be combined with policies aimed at securing regional governance in the country’s eastern regions. It is only after security threats are resolved that the Congolese population will begin to reap the benefits of their resource-rich territory.